The New York Times

Wendesday, April 12, 1995

Book Notes

Award for Ford Stories

By Mary B.W. Tabor

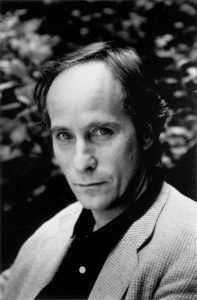

Richard Ford, author of novels and essays as well as short stories, has been awarded the 1995 Rea Award-for the Short Story. The award, which carries a $25,000 prize, is presented each year to honor a living American author who has “made a significant contribution to the short story as an art form.”

In their citation, the three judges—Richard Bausch, Ethan Canin and Mary Morris—said Mr. Ford’s literary power “lies in the deceiving simplicity of has language, in the complexity of the emotions he explores, and in the extraordinary tenderness with which most of the people in his stories go about the solitary business of loving, and seeking love.” Mr. Ford’s collection of short stories, Rock Springs, was published in 1987.

Litchfield County Times

New Milford, CT

May 5, 1995

Rea Award Recipient Chosen

Richard Ford, editor of The Granta Book of the American Short Story and author of four novels, has been chosen to receive the $25,000 Rea Award for the Short Story, an annual prize established by Michael Rea, a retired businessman who resides in Washington.

The award is administered through Mr. Rea’s Dungannon Foundation and given to a living American author, “who has made a significant contribution to the short story.” Rather than applying for the cash prize, recipients are selected by a panel of three jurors selected from the literary world and familiar with the form. Mr. Ford’s stories have appeared in Esquire, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair. His fifth novel, Independence Day, is scheduled to be published in June. He is also the author of a collection of short stories, Rock Springs, which are set in the American West.

The jury cited Mr. Ford’s empathetic depiction of transience in their announcement: “Richard Ford’s power lies in the deceiving simplicity of his language, in the complexity of the emotions which he explores, and in the extraordinary tenderness with which most of the people in his stories go about the solitary business of loving, and seeking love. His stories are exemplars of the form. For their clarity, for their unfailing grace, their intellectual beauty, they deserve to be celebrated.”

This year, Mr. Ford was selected from four nominees. Each juror chooses two nominees apiece, but duplication narrowed the field, explained Mr. Rea, who abstains from the process except to inform the winner. Describing Rock Springs as “a classic” and Mr. Ford’s fiction as, “straight in a line from Raymond Carver,” Mr. Rea said he was “delighted” with the jury’s selection: “He’s a very important writer.”

An aficionado of short fiction, Mr. Rea established the award in 1986 to acknowledge an underappreciated form of writing. Despite their brevity, short stories challenge readers with a nuance of their own, he said, adding, “A good short story has a compression to it, a tightness. You have got to read underneath the lines to get under it.”

Conceding that novels are more lucrative for both authors and publishers, Mr. Rea credits the growth of creative writing programs and a devoted readership for keeping short fiction alive. “I think the short story is healthy,” he said. “The creative fiction writing courses are good. I’m not sure if they make people into short fiction writers, but creative writing is creative writing.”

Although the award seeks to promote short fiction, its founder excludes publishers or other commercial interests from the jury. Mr. Ford is the 10th author to receive the Rea Award for the Short Story. Previous recipients include Grace Paley in 1993, Eudora Welty in 1992, Joyce Carol Oates in 1990, and Tobias Wolff in 1989.

Library Journal

July 1995

Author Insight

Sanctuary for Ideas We Love—and Hate

By Richard Ford

Novelist Richard Ford delivered the following speech to a rapt audience of collection development librarians at the annual Random House/Library Journal breakfast last month at the ABA convention in Chicago. His remarks so moved librarians there that they asked us to publish it in LJ. Ford’s Independence Day (LJ 6/1/95), a sequel to his best known previous novel, The Sportswriter, has just been published to wide acclaim. Ford is also this year’s winner of the prestigious $25,000 Rea Award for the Short Story, bringing him into company with previous winners such as Eudora Welty, who lived across the street from Ford in Jackson, Mississippi. It was there that he developed his passions for the written word, freedom, and libraries.

The library is an institution that stands for and guarantees our freedom—not so much the burly freedoms we’re willing to go to war for (e.g., the putative freedom to impose our governmental forms and economic theories on others, the freedom–by-right to supply our country with oil, the supposed freedom to bear arms) but the more fragile freedoms that in fact make us feel free, not angry and selfrighteous when we exercise them, those seemingly inessential freedoms that make our lives feel rich around us and make us believe we’re lucky to be alive: the freedom to find a book and read it—or not; to experience views contrary to our own without personal threat; to indulge in what might seem inessential in the course of difficult, complicated lives addicted to the seemingly urgent and necessary.

Who hasn’t felt that sense of peculiar freedom that surrounds us upon entering a library? Sometimes it can be quite disorienting to me. Sometimes I can’t stand it and have to leave.

Freedom, of course, is a tricky business, and people are willing to use that word to mean very different things. David Duke certainly means one thing by it; the Free Will Baptist Church in Ecru, Mississippi, means apparently something else. In Mississippi and in Montana—both places I live—citizens occasionally have a highly developed and personal definition of freedom. Freedom often means “my” right to do anything “I” want—no matter what “you” want. Freedom is for “me”; whereas the restraints of law, the rule of the reasonable “man,” the pressing need for moderation in order that calm heads might prevail—that part’s for you.

In a blithe way, this is the impulse that causes those little moronic white frat boys up at Ole Miss to wave their rebel flags in the face of fellow students who are black, and who look on that flag as an emblem not of the other man’s freedom but of their enslavement.

The library, though, represents and assures freedom of this very nature and of our better natures, too. In particular, it assures us access to books we approve of and books we don’t like; to ideas we hate that another person might love. If writers and great literature can be said to engage in a vital quarrel with the culture, the library is the sanctuary for that quarrel—for the liked and the un-liked, for the subversive and the exciting—somewhat protected from the arithmetic of marketing and cost accounting, and protected from those blue-nosed moralizers old and young who think they know what we should read and what we should learn—just because they already know what they fear and what they can’t stand for us not to fear. The library contains these volatile opposites, holds them, gives them an institutional sanction, a safe place, and in so doing cushions them, lets us as a culture hold them safely in our minds as ideas, and of course invites us to decide for ourselves.

Freedom’s an easy concept to grasp and fight for when it’s our freedom, our preferences and ideas, our religions and ideologies that are being respected and financed.

But freedom has moral force only when it is defined—as it is defined in the library—by allowing others to do, read, like, profess, even act upon impulses we don’t like, wouldn’t act on ourselves.

To do other is censorship. As Salman Rushdie wrote, “the worst, most insidious effect of censorship is that, in the end, it can deaden people’s imagination. Where there is no debate, it is hard to go on remembering, every day, that there is a suppressed side to every argument. It becomes almost impossible to conceive of what the suppressed things might be. It becomes easy to think that what has been suppressed was valueless, anyway, or so dangerous that it needed suppression.”

Books are odd and contradictory things, and in need of protection and encouragement and stewardship because they and our recourse to them are so fragile and vulnerable and “small” in their effect but also because books are so potent—as Rushdie to his and our dismay found out when he published The Satanic Verses. This odd, combined characteristic of volatility and almost inessentialness of books makes the library’s growth and maintenance so important.

I was in a way raised in the library. First in the old Carnegie Public Library that was in Jackson, Mississippi, across from the State Capitol, a building Miss Welty memorably photographed in the Thirties. My mother took me there in the Forties. We lived in that neighborhood, on Congress Street. And later, in the early Fifties, when that building was torn down and the new place built on North State Street, she routinely deposited me there on hot summer afternoons because it was safe and cool inside, and the librarians knew her—knew I was an only child and she was often by herself—and they would keep an eye on me.

Not long ago I was visiting a small-town Mississippi library and I was impressed by a sign in the children’s reading room stating the library’s rather straightforward sense of mission: “To introduce children to reading; to assist students of all ages; and to serve as a clearinghouse for information.” It seems very very clear to me and certain, pragmatic, admirable.

In Jackson, in the Fifties, the library had a somewhat expanded and experiential, much less clear “mission” for me—in addition to serving as day care for my bewildered mother.

I remember it all, of course, because as in many families, a child’s exposure to the library is her or his first exposure to discretion, to his or her own freedom of choice in a larger world of choices; it’s the major beginning point to one’s personal history—the thing you drag around with you forever.

In those days there was a kid in my class at Jefferson Davis School who was trying to start—in the way that kids seem to start little clubs—a small Nazi cell group, which he luridly called “The Rebel States of the Reichstag” And there were several of us goats who were his companions who were willing to show up at his house after school and do a lot of plotting and idiotic marching around stiffly, imitating Nazis with Southern accents. This wasn’t long after the end of World War II, and there was a bit of submerged Nazi sentiment in Mississippi among the nitwits and hatemongers who didn’t like anybody and who were feeling paranoid about societal change. Maybe this same guy now works for David Duke down in Metairie since that’s the drum he’s marching to.

But I remember that I went to the library and got a copy of Mein Kampf—it was there! And in my little way, in the fourth or fifth grade, I read it. And I remember thinking how dull it was, how egocentric, how unexceptional. We hated Nazis in my house. And when I brought that book home—a book my mother knew something about—its appearance in our house and in my hands occasioned a rather long conversation that included my mother describing the distinction between Nazis and Germans, included also the beginning of a lifelong suspicion I have for demagoguery and its political rhetoric, as well as founding in me a belief I later learned more clearly from Conrad, that evil so often has its beginnings in the banal. Indeed, it is literature’s as well as the library’s vital mission to remind us to pay attention—to the small things—or else risk missing the very large.

In the library in Jackson I also in a way experienced my first review, in public. Somebody wrote on the wall in the men’s bathroom—“Richard Ford has the dirtiest mind in Jackson” And I had occasion as I feverishly erased those words to wonder if they were true, and so what if they were. I suppose that was the library serving as a clearinghouse for information.

And in the library in Jackson there was also a librarian—a middle-aged man who was the “strange younger brother” of a very prestigious family. And now and then he would walk up behind me, where I was sitting poring over whatever book I pored over, and put his hands on my shoulders and say, “Richard Ford, what in the world are you reading?” And then he would in some almost undetectable way, kiss me. On the back of my head. Just lightly. And then that was all. There was never any more to it than that. And I remember thinking. “Well, gee, okay. that’s strange, isn’t it?” I, of course, mentioned this to my mother—and these were the old days, long before the McMartin preschool trials, and the sexual revolution and the backlash to the sexual revolution—and she just said, “Oh, well. Richard. Just stay away from him. He doesn’t mean anything.” And I did, and he didn’t, and I think about him now with a certain kind of sympathy. And however and from wherever I’ve come by that particular attitude in my life—that sympathy—it’s been a principal purpose of my written work these years to write about people I am sympathetic toward, to locate sympathy and invite it where conventionally it might not seem to belong (that odd man in the library, for instance), and to invite readers within the free and safe confines of a book to do the same.

PALM BEACH DAILY NEWS

April 25, 1995

Rea Award puts value on short story writing

By Jan Sjostrom

Daily News Arts Editor

Michael Rea has been devouring short stories since his college years. His passion for the story has driven him to amass a 400-volume collection of first edition American short fiction.

Now retired from a career in broadcasting and real estate, Rea has become more than a passive connoisseur of stories. He is the patron of te Rea Award, the genre’s largest prize.

In 1986, Rea set up the Dungannon Foundation to finance the $25,000 award, which is given annually to a living American writer who has made a significant contribution to the short story.

“What the money does is give some substance to the short story,” said Rea Wednesday at his winter home in Palm Beach. “This is one of the largest literary award around and certainly the largest short story award. I knew when I started it that by putting that price tag on it I’d get good press, and I did. I’m doing it for the writers and for the craft of writing good short fiction.”

This year’s prize was recently awarded to Richard Ford, author of the short story collection Rock Springs and the novels A Piece of My Heart, The Ultimate Good Luck, The Sportswriter and Wildlife. His short stories have been published in The New Yorker, Esquire and Vanity Fair, among other magazines.

Ford has received a number of awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, two grants from the National Endowment of the arts, and an American Academy of Arts and letters Award for Literature.

Ford said he was stunned when Rea phone him to hell him the good news. Ford thought Rea was calling him to ask him to be a part of the jury that selects the winner.

Ford is in good company. He joins past winners Cynthina Ozick, Rober Coover, Donald Barthelme, Tobias Wolff, Joyce Carol Oates, Paul Bowles, Eudora Welty, Grace Pale and Tillie Olsen.

In Ford’s case, the Rea Award will have the immediate effect its found intended.

“I’ve just finished a long novel. This gives me the spot encouragement I need to say now I can go back to writing stories,” Ford said from his home in New Orleans, the most recent of a long succession of the restless writer’s residences.

Actually, it would not be far afield for Rea to ask a writer like Ford to serve on the Rea Award panel. Rea makes a point of choosing jurors respected in the literary community. Rea does not participate in selecting winners.

“Frankly, the jury is what the award is about,” Rea said.

Rea has learned to steer clear of those with publishing ties who may have ulterior motives for promoting certain writers. This year’s jury consisted of three writers: Richard Bausch, Ethan Canin and Mary Morris. Bausch and Morris also teach writing at the college level.

In selecting Ford for the award, the jury wrote: “Richard Ford’s power lies in the deceiving simplicity of his language, in the complexity of the emotion which he explores, and in the extraordinary tenderness with which most of the people in his sotires go about the solitary business of loving, and seeking love.”

Ford was born in Jackson, Miss., in 1944. He deliberately shunned writing about his home state, a task Faulkner and Welty had accomplished all too well for another writer to try to cover the same ground, he said.

His desire to find fresh material and his natural wanderlust have uprooted him more than 20 times in the past two decades. He has lived in St. Louis, New York, California, Chicago, Michigan, New Jersey, Vermont and Montana, to name a few of his abodes.

His characters often share this rootlessness, be it spiritually, emotionally or physically. The characters are not so much adrift as they are in need, Ford explained. “I try to write about people who are wanting, in the sense of not having and the sense of wishing for something.”

Ford’s recently completed novel is a sequel to The Sportswriter, his most successful book to date. The book was named one of the five best novels of 1986 by Time magazine.

The Sportswriter was built around the reveries of a sportswriter who had suffered a double tragedy: the death of his young son and the collapse of his marriage. The sequel, titled Independence Day, is due out in June.

Ford spent almost four years on the new book. After that exhausting task, he will be glad to return to the short story.

“Anyone who says a short story is as hard to write as a novel has never written a good either one,” he said. “But I wouldn’t want the reader to think that novels are more important than short stories. I’m just thinking of the demands on me as a writer. I exert the same kind of scrupulousness for both.”

That is exactly the kind of writer that Michael Rea wants to encourage.

Sunday Record

Hackensack, NJ

May 7, 1995

Stories short, quality long

By Laurence Chollet

Book Reports

The Rea Award for the Short Story is given annually to a living American writer who has made a significant contribution to the short story form, and this year’s winner of the $25,000 prize is Richard Ford.

“When the guy called me, I was taking a nap,” Ford sad this past week from London, where he is on tour. “And I felt, ‘Oh, he wants me to be a judge for this contest. I guess I’ll have to do it.” But then he said he was giving me the award, and I didn’t know what to say because I haven’t published a short story in a number of years; I’ve been working on this long novel.”

What sets ford apart form pervious winner is that he’s only published one slender collection of shrot stories —Rock Springs (1987).

That was enough.

“Richard Ford’s power lies in the deceiving simplicity of his language,” the Rea jury said. “His stories are exempla o the form. For their clarity, for their unfailing grace, their intellectual beauty, they deserve the be celebrated.”

The Mississippi-born author, who divides his time between New Orleans and Montana, churned out most of his short stories in the 1980’s while writing a long novel, The Sportswriter.

“I sort of wrote the stories in Rock Springs over a seven-year period,” Ford said. “I’d run out of my enthusiasm for The Sportswriter, and I’d take time out and write a story. We were living in Montana at the time, and it seemed like such a fertile ground for writing stories.”

Ford likes to work in the 4,000- to 6,000-word range on short stories, although one recent attempt (Jealous) ran nearly 10,000.

He has no set subject matter, although his characters are often uprooted drifters, moving through sweeping Western landscapes, often desolate and sad.

The key think, he says, is knowing where to start.

“You have to enter the story at the right point,” Ford says. “If you don’t enter it at the right place, then it runs off the rails—it gets all out of proportion, it carries too much baggage, and it has too much time on its hands. … Consequently, I just wait, and wait, and wait until all those bad ideas get out of my head before I start.”

Right now, Ford has just finished up a 451-page novel—Independence Day, which is due out in June, and is ready for something, well, shorter. He hopes to have another short story collection out later this year—if he can get lucky, he says.

“Short stories are kind of miraculous little things,” Ford says. “You have to sprinkle pixie dust on yourself just to be able to write one.”