The New York Times

April 10, 1986

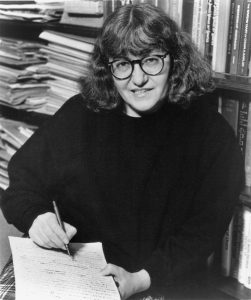

Cynthia Ozick Chosen For Short-Story Award

Cynthia Ozick has been named to receive the first $25,000 Rea Award for the Short Story. The award is scheduled to be given annually to a living American writer whose short stories “have made a significant contribution to this art form.”

Miss Ozick is the author of six books, including The Pagan Rabbi and Other Stories, Levitation: Five Fictions and The Cannibal Galaxy, a novel.

Jurors for the award were Bill Abrams, a book editor and editor of Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards; Shannon Ravanel, editor of Best American Short Stories, and Peter Schmidt, an assistant English professor at Swarthmore College.

The award is financed by the Dungannon Foundation, a private foundation in New York whose president is Michael M. Rea of New York and Palm Beach, Fla.

Gannet Westchester Newspaper

May 25, 1986

Cynthia Ozick — in short

Author helps keep the short story alive

By Steve Bornfeld

Staff Writer

There is no substitute for the short story, says award-wining short story writer and novelist Cynthia Ozick of New Rochelle.

“The short story is like a poem, a unique form. A novel can’t do what a short story does. A short story makes a world happen in its own way. That doesn’t mean what it tackles is a smaller thing. It can really be a saga. It sees all it wants in a whirlwind. I novel unfolds, but a short story is alike a vision. It starts out with the end in its pocket.”

Ozick, 58, is a master of the form: Four of her six books are collections of short stories. Her short story collections include The Pagan Rabbi & Other Stories, Bloodshed and Three Novellas, Levitation: Five Fictions and Art and Ardor: Essays. Her work has been included in Best American Short Stores, published by Houghton Mifflin, in 1970, 1972, 1976, 1981 and 1984.

Her latest honor, attached to a $25,000 check, is as the fist recipient of the Rea Award, a new prize to be awarded annually for American writers who have made “significant contributions” to short story literature. It was established by Michael M. Rea (pronounced ‘Ray’), president of the Dungannon Foundation, a family foundation that exists solely to bestow the award.

“The short story is important to me, and the timing is right. I think that right now, the American short story seems to have a kind of rebirth in writers and publishing,” said Rea, 59, a retired New York City businessman and short story author. “I would be 100 on to encourage them to sit down and write another collection of short stories. I’ll feel the award is worthwhile.”

Rea’s congratulatory phone call to Ozick caught the honoree off guard. “I really couldn’t take it in,” Ozick said. “I thought it was some kind of hoax. I couldn’t hear it. There was no way to assimilate it. He spoke it again, slowly. It finally sank in. I think I was as close to being numb as I’ve ever been.”

Ozick was elected by a three-member jury comprising Shannon Ravanel, a Houghton Mifflin editor; Peter Schmidt, an assistant professor of English at Swarthmore college; and jury chairman William Abrahams, editor of the Prize Stories: The O’Henry Awards.

In an essay commending Ozick, Abrahams saluted Ozick’s short story collections but paid particular tribute to “The Shawl,” a five-page story, written in 1980 , about a woman held prisoner in a German concentration camp during World War II who conceals her baby under a shawl. The child is discovered by a camp guard, who flings the infant against an electrified fence as a horrified mother looks on.

“An inspired writer has conveyed to us in a few pages a moment of life and death, fragments seized form an unspeakable human tragedy and translated into an image that cannot be obliterated” wrote Abrahams. “Reading ‘The Shawl,’ we are moved past the truth of fact to a deeper, different understanding. We bear witness to the truth of art.”

Ozick said she is generally opposed to creating fiction out of massively documented events such as World War II but was struck by a sentence about an electrified fence in a book about the war.

“I had this seizure,” she said. “The short story usually comes form an idea. I know writers who begin with the psychology of a character. The scene unfolds. That can happen to me, too. But at least with the short story, it’s not an event, not seeing a moment, but an idea, a philosophical idea that seizes and seems to throb, and characters grow out of the idea and characters.”

Although many American writers are still penning off in the face of television, which tells stories without taxing the imagination, such a necessary ingredient of short story reading. As an avid reader and aspiring writer growing up in the Bronx, Ozick recalled the abundance of those compact tales.

“RIDING THE SUBWAY to school as a teen-ager, I could read a whole short (story), if the person next to me were holding a paper so it was facing me,” she remembered. “In the tabloids, it was hack work, but in its own way it was an art form . . . And magazines like The New Yorker have been faithful to the short story forever. Where a magazine has been faithful to the short story, there is a little eternal right o faith burning somewhere.”

Whatever she sets her pen to, whether it be short stories or her two novels, “Trust” and Tithe Cannibal Galaxy,” Ozick feels the pain of her art. The phrase “good enough” has a hollow ring for her.

“You always feel you’re falling short of perfection you can never reach,” she said. “I’m a perfectionist. But there’ another kind of pain. Not just of making a sentence, but going on a trip to a bookstore or public library, standing in the great cathedral of art and seeing how puny one is. That’s painful,”

Such an experience keeps a writer’s ego in check, something Ozick said is vital during the creative process. “There has to be an enormous distancing,” she said. “If yourself is in there (the work), it won’t become what you want it to become. What happens, though you are your own play, at best, is the total annihilation of the self. If you don’t achieve that, if there’s the slightest shred of ego, you will inevitably fail. You must enter totally with a work of imagination.”

The writing life has condition Ozick as a night owl. Between 11p.m. and sunrise, when most of us are lost in dreams, Ozick shifts into creative overdrive. “The world really isn’t there. It is a kind of waking sleep. The imagination can stalk in utter freedom. No one will interrupt you.”

And in the stillness, Cynthia Ozick is the ruler of all she surveys in the kingdom of her imagination. “You can drive off into the depths of this world where the writer can make the reality. Where one governs one’s own little universe.”